Feel your entanglement with everything

In the middle of all of this absolute shit, I have been thinking about how Dawn Cerny's art tickle-wrestles with wealth, status, and formality.

Something — everything? — is plainly very wrong. This is the basic fact I have been awakening to for some years since I began to notice that I have been born into a body and a place in history where I am benefiting from a world that is hurting other people for my benefit while making me believe I am separate from this hurt, lonely and autonomous and unentangled. It is this context in which I am trying to write now — a context in which something, maybe everything, is plainly very wrong, and it does not seem enough simply to resist. I am trying to consider how to reimagine.

In the dictionary, the word “folly” is defined as a “lack of good sense; foolishness.” Then again, is it wise to follow whatever is considered “good” sense in a world like this one? Back to the dictionary: The secondary definition of “folly” is the one that Dawn Cerny, the artist, is referring to when she says she began her latest show in Seattle with folly: “a costly ornamental building with no practical purpose.” Thus, making a folly means making something that does not serve the categories of the world as it is. It is a structure or campus of structures without an existing client; maybe, it is a form open enough to create a new kind of client, and new relationships between its new clients.

Cerny’s exhibition is this kind of folly, a series of forms providing stages for different kinds of relating. The typical format in museums is that the relating is taking place between precious objects inside frames and cases and bodies scraped of unruliness. The snot, sweat, tears, blood, heat, and noise of bodies have to stay out of the carefully climate-controlled and security-guarded galleries. Despite decades of attempts by some museum workers to make people feel more at home at museums, museums, largely due to the reality that they are modern-day treasure troves, cannot easily engender the kind of relating that we can do in our homes. This is a problem for artists, who might like to make a living through their work but might not want to do it by creating objects that then migrate to rarefied worlds and leave behind a more entangled, more embodied version of relating. “Who am I and who are you and who are we together?” Cerny kept asking when she was giving her artist talk about this latest show at the Frye Art Museum. Artists are not the only ones asking these questions now, about how to imagine and live out futures beyond a hyper-capitalist system that so aggressively reproduces its own logic, co-opts resistance, and hides the violence of its relationships.

This is a world full of shit, and we need to work together to compost that shit, as Vanessa Machado de Oliveira writes in her 2021 book Hospicing Modernity. It’s a challenging book, so she and the Gesturing Towards Colonial Futures collective provide a series of encouragements to help readers navigate, a few of which stand out as I think about Cerny’s work:

“Feel your entanglement with everything, including the ugly, the broken, and the messed up. Relate beyond desires for coherence, purity, and perfection. …Renounce fantasies of comprehension, consensus, and control. …Let go of the fear of ‘being less,’ the pressure of ‘being more,’ and the need for validation.”

I’ll start with the waste baskets Cerny made. They look like line drawings come to life: she weaved webs of wire and joined them with fat nodes of melty metal epoxy, then painted the webs in bright, saturated colors and clad them in pastel trash bags. I’d never really considered before that museums and galleries never have waste baskets in the rooms with the art. Like, ever. Of course they don’t. (Feel your entanglement with everything, including the ugly, the broken, and the messed up.) Cerny joked, “So the waste baskets are just about representation,” and yes, we in the audience at the artist talk laughed at this ridiculous thing to say, but my laugh was chased by the thought, well, don’t tell the feds that Seattle has DEI for trash cans. Back in the galleries, I was curious whether anyone had thrown any actual waste into the baskets. Seeing a crumpled-up tissue in one, I felt a little jolt of joy. Someone, knowingly or not, had loved that art enough to transform it into a relatable object using real trash, and now I was loving their tissue as something precious. There are so many moments like this in Cerny’s work, sneaky little currents of relationships transformed.

I keep thinking about a woman who was there the day I first visited in February. Walking in with friends, she let out a little scoff. And why not? To me, she was picking up the full spectrum of what the art was putting down. It’s art that leads with oddness and an almost embarrassing exuberance, using various types of awkwardness to evoke initial doubt, as in, is this artist fucking with us? I grieve a little that after years of looking at Cerny’s work I can’t experience that initial doubt anymore; I trust her too much, maybe. But I think the work uses that initial doubt as part of its action.

“My work is the Jerry Lewis to the Dean Martin,” Cerny said, and she filled two empty galleries of the museum with her own work but also added her slantwise interventions into the adjacent gallery where the Frye displays its permanent collection of century-old gilt-framed paintings, uncovering, in the process, that a museum collection is a heck of a straight man.

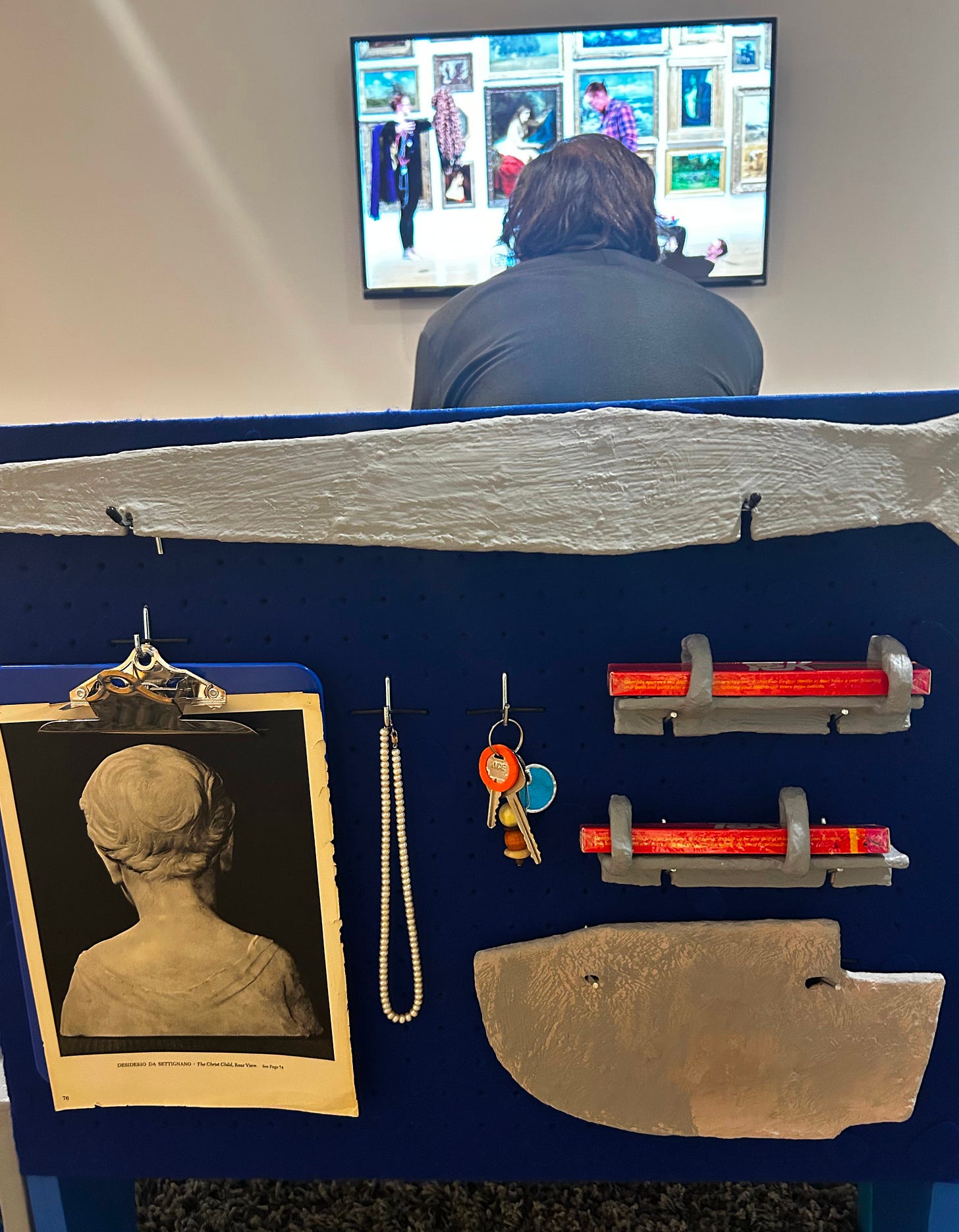

Into the empty, rotating galleries adjacent to where the permanent collection is on permanent display, Cerny inserted mini domestic settings, fragments from home translated. Using pastel-colored sheer curtains lightly blowing in the HVAC, she separated the fragments to theatrical, dreamy effect: low-budget magic. A sitting area, an entryway with a coat rack, or a sofa set in front of a TV mounted on the wall — each domestic zone is now materialized in the museum reinterpreted into Cerny’s lumpy, vivid language. It seems to me that she is trying to make real furniture that works, as in it supports your body, but also that can offer you something besides a standard or an ideal to relate your body to. (Relate beyond desires for coherence, purity, and perfection.)

Walking through is a subtle game rather than a coherent system. Some of the mini-scenes are places you can enter, relax and put your feet up, literally, as with the gossip chair in the center of the permanent gallery collection (Cerny’s interpretation of the Frye’s own velvet fixture) or the sofa where you can watch the artist’s videos on the TV. Other times, Cerny’s setups are sculptural installations only to be admired from that classic museum distance, no different in appearance from their neighbors but nevertheless — nonsensically, or other-sensically, if we are to agree that we can no longer agree on “good sense” in a world like this one — cordoned off with lines on the floor and the injunction “DO NOT TOUCH.” For titles, Cerny made little poems: Varicose Blossoms for No Man; Kleenex Side-table for Simone Weil; The Edith Wharton You Can Afford.

In her impulse to unearth and play around with relationships, Cerny finds such a good foil in the Frye because of its specific history.

Charles and Emma Frye were children of German immigrants who rose to fortune through their meatpacking business in Seattle in the late-19th/early-20th century. Their approach to art remained more 19th century than 20th. They bought art for their home starting in 1907, much of it German and/or pastoral/animal-related, only later deciding they would endow their city with a museum and nest their art inside it. Their collection is irregular rather than coherent in part because it’s personal and domestic; it reflects them in all their glories, anxieties, and foibles. At home, the Fryes hung their art salon-style. It crawled the walls, packed tight, individual pieces less the point than the awe-inspiring effect of the whole. In the middle of their home art gallery, they installed a velvet three-way gossip chair so that viewers could check out the view from every angle, survey it like a vast landscape.

For the last few years, the Frye has chosen to install its founders’ collection the way they did it at home, including the chair. This way of relating to art has its own effects. It creates a different experience than the single-file parade of art we see in any given museum today (which is an artifact of the intellectualizing, atomizing, evolutionist, meritocratizing ethos of modernism — you can maybe tell I have mixed feelings about both modernism and the salon as setups for relating to art). The salon style drips with robber-baron excess, especially in this format with these big gilt frames, but it’s also more embodied and entangled, surrounding the viewer with weather and chatter, offering choose-your-own-adventure storytelling. Seeing it I’m reminded of another zone of relating that has been white-and-uptighted: the shut-up-and-sit-in-the-dark world of “classical music” as we have come to know it, which once was more a place where they sold beer and sausage in the aisles, kept the lights sparkling, and sometimes talked over the musicians. This is not to romanticize; in her videos, Cerny’s hilarious attempts to insert herself into the Fryes’ paintings are a reminder that art, regardless of how you display it, has often been a vehicle for, and a reproduction of, the consumptive energy of the powerful. For her version of the gossip chair (there have been several wonderful takes on this chair at the Frye over the years), Cerny added Easter eggs in the form of reading materials, expanding the interlocutors involved in the gossip. Cerny also connected the galleries she put her own work into with the permanent collection salon by cutting a big hole out of the wall between the two, so that each side is framed and included, like an added work, in the middle of the other.

The modest materials Cerny uses are directly at hand in her life as a mother and adjunct art instructor: paper, yarn, coupons, dish towels, rubber bands, the wild, furry geometry of rag rugs. The furniture sculptures are made of wood scraps coated in paint, the overtly inexpert construction itself a kind of slapstick. The sculptures “begin with the notion that ‘furniture’ and ‘mother’ are figures that secure a value (to others) for their potential to hold, display, or be absent-mindedly left with things,” Cerny writes in an artist statement. Freestanding wall works most readily identifiable as art objects gesture toward cabinetry or utility shelving, draped in household objects yet also mounting beautiful ink and graphite drawings. Every piece bears the lumps and bumps of a middle-aged human body.

The most overtly absurd works are the videos in which the artist performs. Back to my fellow viewer: on her first time through the show, the videos drew her loudest scoffs. But the videos were also the site where she finally broke into laughter and a kind of conspiratorial nodding after she had been through the permanent collection gallery and come back to the videos, having seen the whole act, as it were, of this particular Lewis-and-Martin routine.

This is what Cerny’s work does, building a nervous tension that splits open into comedy. Another way of looking at her work that came to me as I was watching this other woman was that it hits like milk that builds up in a mother’s body before it lets down. At some point, something clicks. The work is earnest, hardworking, and handmade. And the artist’s hand does not do all things with the same level of polish. Her drawings are hauntingly beautiful and make drawing look easy, almost naturally occurring. By contrast, her furniture makes it look like furniture is difficult to build. All this, too, is about relationships, for one the relationship between two dimensional art (easy to love, easy to display) and sculpture (bulky, difficult); and for another the relationship between the artist and what she makes (master/beginner, inventor/replicator/gatherer). Look long enough, and you can’t help but recognize that there is method to using wit, elbow grease, and throwaway materials — the stuff of a middle-aged mother working on borrowed time in her basement — to tickle-wrestle with wealth, status, and formality; to emphasize and experiment with her entanglements as an artist. (Let go of the fear of ‘being less,’ the pressure of ‘being more,’ and the need for validation.)

I remember the first time Cerny had a museum show. It was 17 years ago, at the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle, on the eve of when her brother, a young soldier, was in training to be sent to war by another liar president. Cerny printed toy soldiers out of paper and set them on the floor to battle it out as we looked down and watched from a suddenly uncomfortable height. Nearby, she had created a sitting area she thought of as a waiting room. It had a box of tissues (tissues are on display in the new show, too, Cerny’s faithful agents of the effluvia and emotionality commonly banished from view). We’re All Going to Die (Except for You) was the title of that earlier show. When it really comes down to it, when you get the feeling that you are a messy little bodied self set against the forces of life and death and history, what do you want to do? Play, laugh, panic, cry? I imagine the artist nodding in answer, lots of nodding, nodding that begins to turn antic. (Renounce fantasies of comprehension, consensus, and control.)

For this show, Cerny said, “I started with folly…something nobody even asked for, [something] for pleasure, slight and comical and fun. And yet this is how we make the future. At the core, it’s a very earnest fight.”

Gorgeous response to a deliriously enigmatic offering. As usual with Jen, who is just the best...Ren W